Défis Humanitaires presents a summary of the fifth edition of ALNAP’s State of the Humanitarian System Report for the period 2018-2021. The report, published every four years and written by nearly 70 contributors, provides a comprehensive picture of the size and performance of the international humanitarian system based on qualitative and quantitative data from humanitarians and beneficiaries, academics and policymakers. This includes evaluation summaries, quantitative analysis, field surveys and interviews (5487 beneficiaries and over 100 humanitarians interviewed in six countries) and analysis of their database covering a 12-year period. The methodology of this report enables comparisons with previous reports, allowing for more than 15 years of insight and analysis to assess the needs of the sector. This edition answers 12 questions on the state and functioning of international humanitarian aid. We present here a summary of the report with a link at the end to the full report.

The international humanitarian system is comprised of entities that accept international funding and identify with humanitarian norms or principle. They operate in a wider context of other sources of support for crisis-affected people. Between 2018 and 2021, the global figures of people in need rose by 87%. The COVID-19 pandemic drastically altered the scale and geography of humanitarian need and the capacity of economies to support populations at home and abroad. The pandemic’s social and economic shockwaves resulted in an estimated 97 million people pushed into extreme poverty in 2021. At the same time, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) found strong evidence that climate change is contributing to complex humanitarian crises. The number of conflicts more than doubled over in the last decade to 2020 and continued to rise. The number of people living in forced displacement has grown every year since 2011, reaching 89.3 million in 2021

Part 1: What is the shape of the humanitarian delivery system ?

There are an estimated 5000 organisations in the humanitarian system in 2021, which is 10% higher than estimates a decade ago. This can be explained by the growth in the numbers of NGOs and local NGOs. Despite the growth in the number and diversity of NGO, the bulk of humanitarian aid continues to flow through UN agencies.

Total funding for international humanitarian assistance in 2021 was nearly double what it had been a decade before but largely plateaued over the 4 years between 2018 and 2021. The number of humanitarian staff working in crises-affected countries has more than doubled over the past decade due to the growth in humanitarian funding, the rising scale of needs and the number of countries with a coordinated international humanitarian response. More frontline staff brings more operational capacity but also more exposure to risks.

More than 630 000 humanitarian staff were estimated to be working in countries with humanitarian crises in 2022 and over 90% of these staff were nationals of the countries they were working in. On average, UN staff were paid more than double their INGO peers and staff of international organisations as a whole were paid on average more than 6 times the salary of local/national NGO staff.

Many INGOs have put in place policies, strategies, and training programmes to increase the diversity of their staff and address the systemic issues hindering recruitment. The sector is doing better on the representation of women in senior positions. However, when it comes to the leadership position for people from countries receiving humanitarian aid, progress is more limited. While agencies employ a large number of national staff, it appears that only a minority make it to country director level, let alone to HQ leadership positions.

How well does the system engage with other forms of crisis support ?

Survivor/citizen/community-led crisis responses are efforts to respond to humanitarian need that are led and managed specifically by survivors and communities form crisis-affected populations themselves. This type of assistance overlaps with locally led humanitarian assistance and participatory humanitarian action but is unique as it includes efforts that are not part of an institutionalised humanitarian programme or supported by specific funding. Faith-based international NGOs have long worked with local networks and religious leaders to provide a timely response and connect with communities. Many humanitarians see the potential value of more strategic partnerships but the incentives driving private sector actors remain poorly understood in the humanitarian space which leads to concerns about ethics or resource competition. Finally, key development actors have also noted that a knowledge gap remains concerning which approaches and instruments are effective in engaging the private sector in fragile and conflict-affected setting country.

Diasporas are also an important source of support for their families and former co-nationals affected by crisis. Outside of remittances, diaspora communities relied heavily on social media to connect with crisis-affected people in their countries of origin. Humanitarian agencies’ attempts at coordination with diasporas have been limited because of the difficulties identifying representative actors among diaspora groups and a lack of trust in international aid institutions among diaspora groups.

What are the impacts of funding shortfalls ?

In 2021, 39% of survey respondents said that they were satisfied with the amount of aid they received compared to 43% in the previous study period. Aid recipients identified ‘not enough aid’ as the biggest barrier to receiving support. The recipients’ views of sufficiency are based on the level of support that comes out of the system, not the amount of funding that goes into it. There is a clear link between how well humanitarians engaged with aid recipients and how satisfied those recipients were with the amount of aid they received. As such, communicating with people is fundamental to increasing trust and satisfaction. Evidence on the impacts of underfunding revealed a dilemma: humanitarians either had to reduce the numbers of people they reach or compromise on the quantity/quality of support they provide.

Part 2: What is the system achieving ?

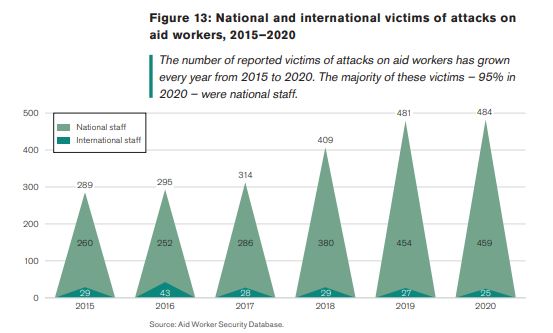

In 2021, the system reached an estimated 46% of the people it identified to be in need and 69% of those it targeted for assistance. Only 36% of aid recipients surveyed thought that aid went to those who needed it most. The largest populations in need were in Ethiopia, Yemen, DRC and Afghanistan. Threats to the humanitarian space – attacks on humanitarian workers continued to rise by 54% between 2017 and 2020 – remained a major barrier to reaching populations.

How well do humanitarian agencies understand people’s priorities?

The survey of aid recipients finds that those who said that they were consulted before assistance was given were more than twice as likely to say that it addressed their priority needs than those who said they weren’t consulted. The majority of aid recipient and humanitarian practitioners interviewed still felt that humanitarian needs assessment largely failed to consult communities sufficiently or effectively. The lack of proximity to affected communities is a recurrent problem for many IOs which was further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

There are many reasons why assessments and analysis continue to fall short, from poor methodologies and analytical rigour to time and political pressures. The gap between assessment and intervention is due to operational constrains that limit programming options. There is also a problem of scope and function – the conflict of expertise between what humanitarian actors believe to be right for people and what people want for themselves. Moreover, there were particular concerns about the involvement of marginalised groups: the voices and needs of youth and marginalised groups are still largely absent from decision making on humanitarian responses. Finally, the environment in which humanitarians intervene often limits what is offered and provided to people in need. In highly constrained environments, blockades, directives, and other impediments are preventing delivery of certain provisions such as medicines, telecommunications and water systems. In refugee contexts, host government policy can limit the possibilities of programmes for refugees.

Where the authorities are market allow it, cash and voucher assistance can give people greater scope to meet their priority needs in the way they deem the most appropriate. The report shows that according to their interview and research, people in refugee camps said they preferred cash as it is more dignified and allowed them to priorities and plan for the future. Yet, practitioners and recipients agreed that cash is not inherently aligned to what people need and can suffer from the same consultation deficits as other forms of aid.

Humanitarian actors need to make sure that their aid is relevant and tailored to the needs of marginalised people. There are persistent gaps with regard to tailoring aid for women, girls, older people, people with disabilities, and LGBTQ+ individuals. There has been notable engagement in the matter with strategies and frameworks being laid out to ensure the relevance of aid. Therefore, organisation now have clear frameworks for adapting their offer to specific groups, yet this has not been systematically translated into programme design. As a result of this gap between strong policies and operational realities, good practice is fragmentated and inconsistent. The pressure that came with the Covid-19 pandemic also have reversed improvement and shifted priorities, from menstrual hygiene for women and girls to food and shelter for instance in Lebanon. The report also highlights concerns that guidelines on inclusion fed into rudimentary and identity-based assumptions about people’s vulnerabilities and needs. These shortcomings can be explained by time pressures within organisations and the lack of knowledge among operational staff as well as funding constraints.

Does humanitarian action adapt to people’s changing priority needs and does it work?

The humanitarian system still struggles to stay relevant as crises persist and evolve and as people’s needs and priorities shift. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, agencies and donors were quick to adapt existing programmes to the new realities of remote working and public health requirements – but this was not the same as adapting to people’s priorities. The report, in accordance with the previous one, find relevance diminishes as a crisis progresses beyond the initial emergency phase. This underpins the case for the renewed focus on strengthening the humanitarian-development-peace nexus. The scope of humanitarians to act in protracted crisis is also limited by competing priorities, constrained resources and political impediments.

Today, there are stronger evidence of the system’s effectiveness in achieving outcomes and improving the well-being of crisis-affected people as it has invested in technical capacity, programme quality and evidence gathering. Improvements are still needed in accountability and participation. Despite the main goal of humanitarians to save lives, there has not been any concluding results showing a decrease in mortality rates. Out of a sample of 29 humanitarian responses, only four had consistent mortality data year on year (the lack of data could account for this result). Across multiple sectors, humanitarians paid more attention to the quality of programming, referring frequently to minimum standard frameworks, monitoring and evaluations. Overall, the system is not as fast and effective as it could be. Indeed, the system’s operational capacity to respond early is not matched by an increase in well-times and flexible funding and when it acts quickly, it relies on less funding which results in inadequate responses.

The evaluation of the system’s effectiveness – does it work? – is difficult because of the lack of consensus on what humanitarian action should achieve. Expectations on the system’s achievements have changed with a greater emphasis on dignity pushing the system to address a wider range of needs, a rise in protracted crises straining humanitarian capacity, and a greater diversity of perspectives on what humanitarian action should look like in the 21st century. Defining effectiveness in terms of meeting objectives offers a limited perspective on the achievements of humanitarian action as aims are often poorly stated and tend to focus on what agencies do in the short term rather than long term.

Does humanitarian action protect people from harm?

Humanitarian protection is concerned with reducing the risk of physical and psychological harm facing people in crisis. The scope of humanitarian protection has led to confusion over what protection looks like operationally and protection outcomes are often poorly defined and shaped by factors outside humanitarian agencies’ control. During the study period of the report, protection was increasingly prioritised in responses (on paper). However, a lack of common understanding, weak leadership and accountability, and overly complicated coordination infrastructure amongst others, have limited the implementation of efficient protection. Protection leadership improved in some contexts but remained absent in others, including during the COVID 19 pandemic. Some form of engagement has been undertaken in several conflict-affected contexts, yet protection of civilians remains an area of weaker global progress compared to protection against Gender Based Violence (GBV) and child protection. Finally, the programming of protection has been hard to evaluate because of the difficulty to attribute responsibilities between humanitarian and other actors.

One of the most flagrant harms from humanitarian action is sexual exploitation and abuse by aid workers. The #AidToo movement brought attention to long-running sexual harassment within the humanitarian sector, prompting new high-level awareness of the gaps in PSEA implementation. The report highlights a push towards hiring dedicated prevention of sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment (PSEAH) staff, driven by donor compliance requirements. Yet, 60% of survey respondent still rated PSEAH implementation as only ‘Fair’ or ‘Poor’. Overall, in many countries, survivors’ assistance is inadequate and hampered by a lack of dedicated resources or inter-agency mechanisms that can facilitate referrals to PSEAH services. Time has shown that change is possible when the system, works together at technical and political levels to make new commitments and design the mechanisms and ways of working needed to deliver on them.

Is humanitarian action ‘green’ ?

As the system is attempting to save lives and protect crisis-affected people, the humanitarian system risks damaging the environment through its presence and wider carbon footprint. data on the effects of the system on the environment is limited with a lack of consensus among agencies on how to measure carbon footprint. Agencies feel like there is a trade-off between addressing people’s immediate physical needs and addressing longer-term environmental concerns. Refugee responses with large-scale camps have caused some of the worst documented environmental impacts: lack of green spaces, limited waste management and low air quality in camp settlements in addition to illness and death caused by polluted water.

An emerging area of success in the system, is increased appropriate and efficient fuel use in programmes, particularly in displacement contexts. Contrasting with the previous reports, many agencies have developed policies and hired staff to improve sustainability and reduce environmental harm: efforts are underway. Yet, the prediction by aid practitioners and host governments in the 2022 SOHS surveys that climate change is likely to be the biggest external threat facing the humanitarian system in coming years.

Part 3: How is it working?

Does the system treat people with dignity?

In surveys, aid recipients were largely positive about their sense of dignity: on average 73% of aid recipient surveyed the SOHS survey reported that they felt that aid workers treated them with dignity. However, in focus group discussion and long-form interviews, responses were more mixed. Affected communities who were consulted about the aid they receive were 2.2 times more likely to say that aid addressed their priority needs, 2.7 times more likely to say that the aid they received was of good quality and 2.5 times more likely to say that the amount of aid was sufficient. Demographic factors also played a role in people’s feelings of dignity. Women and people under the age of 24 were more likely to report being treated with dignity in the SOHS survey.

Overall, the most dignified form of support agencies can offer is simply giving people what they say they most need. As shown previously, programme modalities that support self-reliance and recipients’ agency in their own recovery such as cash, education and livelihoods support are commonly preferred. Even the effectiveness of those programmes depends on how they are carried out.

Does the international system enable local action?

The last SOHS reports mark the beginning of addressing concerns over the system’s performance in complementing and supporting national and local efforts at responding to humanitarian needs. Since then, ‘localisation’ became a key issue for humanitarian agencies due to both the practical necessities arising from the pandemic and the moral necessity prompted by reflection on the humanitarian system’s colonial past. Yet an increase in rhetoric and attention is rarely paired with immediate meaningful changes in practice. As such, despite investments and advances, progress has been much slower and uneven than desired, showing the need to better address the gaps between global-level policy discussion and country-level realities. The Grand Bargain workstream on localisation was seen as the key driver of progress at a global level, providing momentum to international agencies’ policies and mechanisms for localisation. At a country level, agencies held varying interpretations of what supporting locally led humanitarian action meant in practice and there was disagreement about the goals of these efforts. For some it meant localising the international humanitarian system through the devolution of power and resources and for other this view maintains echoes of colonialism. Localisation is also shaped differently in each response by the country dynamics of the country-level humanitarian system and its wider context.

Direct reported funding to local and national actors was volatile over the 2018-2021 period, fluctuating between a high of 3.3% and a low of 1.2%.

Indirect funding remains difficult to track globally due to poor reporting, yet official figures show that indirect funding remains low in 2021. Between 2018 and 2021, almost half of all international humanitarian assistance received by local and national actors occurred in just 3 countries – Yemen, Syria and Lebanon – and three sectors – health, coordination and support services and food security. More generally, the system’s failure to financially support local actors continued to raise important questions of equity as the lack of direct funding perpetuates inequalities in the system. The most significant barrier to increasing the volume of funding to local actors was the perceived inability of many L/NNGO to meet donor accountability and compliance expectation, and the lack of support for strengthening the systems required to do so. On top of difficulties in funding local actors, in the period since the 2018 SOHS, many crisis-affected states chose to take power away from agencies to exercise greater control over how humanitarian response is delivered and by whom. This resulted, in some context in straining the relationship between international agencies and government. UN agencies have tended to have relatively strong relationships with movement where the political situation allowed, yet the quality of UN capacity strengthening initiatives for government staff was considered poor. The SOHS survey of respondents to the government largely reported that poor communication and consultation with host governments was one of the biggest weaknesses in the international system.

International and national NGOs alike see technical capacity-building as valuable step in shifting greater responsibility to local actors, yet some have questioned the framing of capacity as being overly compliance-focused and reflecting the priorities of Global North donors and agencies. Local actors said that capacity continues to be defined primarily by international agencies and expressed a desire to have more say in defining their capacity needs. The quality of partnerships was mixed, but potentially showed improvement. A large majority of practitioners felt that the opportunities for leadership and participation of local actors in decision-making forum in their context were either poor or fair. Both international national staff reported that partnership agreements treat L/NNGO as sub-contractors, their skills and knowledge relegated to the implementation of projects. Moreover, there was a push to include local and national actors more in formal humanitarian coordination mechanisms with clear progress made. NNGOs comprise 44% of cluster coordination membership globally in 2020 and there were also improvements in the use of appropriate local languages in coordination meetings. Despite improvements, leadership roles for L/NNGOs in coordination mechanisms remain rare.

CASE STUDY: LOCALLY LEF HUMANTIARIAN ACTION IN SOMALIA AND IN TURKEY

Does the system uphold its principles?

In the face of grozing constraints, restrictions, and attacks on aid, humanitarians found it ever harder to practice their ideals of humanity impartiality, neutrality and independence. Instead, agencies often defaulted to an ‘access at all costs’ imperative, accepting compromises to their principle as the necessary price for operating in heavily controlled context. Compromises are inevitable as humanitarian organisations try to find a middle ground between principles and pragmatism. Overall, 45% of aid practitioner responding to our survey said that respect for humanitarian space had declined.

The principles are stated as guiding norms for most organisations and most practitioners responding to our survey underscored the importance of humanitarian principles for their work and yet there was limited practical support to put them into practice. There is a lack of clear policies, strategic direction and operational guidance which resulted in a poor understanding of humanitarian principles. Fear of expulsion had a chilling effect on the sector’s collective willingness to speak out about abuses of civilians and blocks on aid. At the same time, interpretation of the principles continued to be debated and revisited. New notions of solidarity have been posited and question of the ‘anthropocentricity’ of humanitarian principles in an age of ecological emergency.

How are agencies balancing advocacy and presence?

Recognising the reduction in humanitarian space and the challenges that the international community faces in negotiating humanitarian access in many settings, in 2021 the Emergency Relief Coordinator announced the establishment of a new unit in OCHA to support ‘smarter access’ approaches. This aims to strengthen humanitarian engagement and provide opportunities to leverage relationships to facilitate humanitarian access.

In the last years, there were recurrent tensions between speaking out about abuses and staying to deliver aid, especially in countries with strong government control where agencies had to choose whether to pay the price for taking a public stand against violations of human rights and humanitarian laws. Analyst also noted an erosion of global consensus on the importance of international humanitarian law in setting limits to war. Connection and collaborations between international, national, and local organisation were also marked by misalignments in power, priorities and policies which undermined collective advocacy. As a response to these shortcomings, there were new efforts by humanitarian agencies to join forces with experienced advocates from other sectors. Protection advocates noted a new creative pragmatism around working with human rights actors to minimise operational risks while maximising the impact of their advocacy.

The challenge remains how to maintain humanitarian principle of independence from donors’ political agendas. Humanitarian funding is often informed by and entwined with foreign policy and domestic objectives including asserting soft power, countering terrorism, and limiting migration. The gap between funding and needs and the continued reliance on a small number of funders make it difficult for organisations to assert their independence. Migration management agendas also compromised the independence of humanitarian action.

Conclusion: Is the system fit for the future ?

As the full report describes in detail, the conditions for delivering effective, efficient, and principled humanitarian assistance grew considerably more difficult over 2018–2021. Although the sector is rife with self-critiques, it has proven again that it can be flexible and successful in facing major new challenges and supporting people through crises, scaling up and adapting. As the world around the system is changing more rapidly, there are questions as to whether it can keep up. Is the system set to meet potential future challenges?

Moreover, global shifts suggest more people will be affected by extreme food insecurity, conflict and disaster. Indeed, deprivation associated with worsening poverty is likely to be a cause and consequence of these crises. The rise in extreme poverty and exposure to risk do not automatically mean an increase in the number of people requiring support from the international humanitarian system. Indeed, social protection systems and disaster risk management systems can adapt and represent safety nets for people. Yet even those safety nets can become under stress. whether the humanitarian system can address an increased caseload is a question of capacity and question of limits. A growing humanitarian caseload will heighten dilemmas between reaching the most people and the people most in need and doing so in a way that better takes account of their views. Re-sizing the system efficiently for the future is more than increasing resources, it is also re-evaluating the scope of its ambitions and its role in relation to others.

A clear message emerging from the report of the past four years is that the basic norms that underpin humanitarian action are under stress. Stress in being felt in economic as well as political spheres which influence each other. The relevance and influence of the Western-led aid model is also in question. If colonial legacies continue to be challenged and the political contours of a multipolar world become more starkly defined, the role of aid may have to change.

Eva Miccolis

You must be logged in to post a comment.