At the end of last year, the OECD’s final data on Official Development Assistance (ODA) in 2021 was published. It is a long process that analyses each year more than 250,000 projects or allocations reported by donors to qualify as ODA. This lengthy process ensures the quality of the figures and explains why only 2021 data is available. It is not a tool for immediate measurement of crisis response, but a tool for analysing trends on a common basis.

In 2021, therefore, all public and private, bilateral and multilateral donors reporting to the OECD spent $222 billion on development cooperation, down slightly from $224 billion in 2020. The 31 DAC members still account for the majority, or 61% of ODA, with an additional effort on their part in 2021, rising from $129 billion to $136 billion between 2020 and 2021.

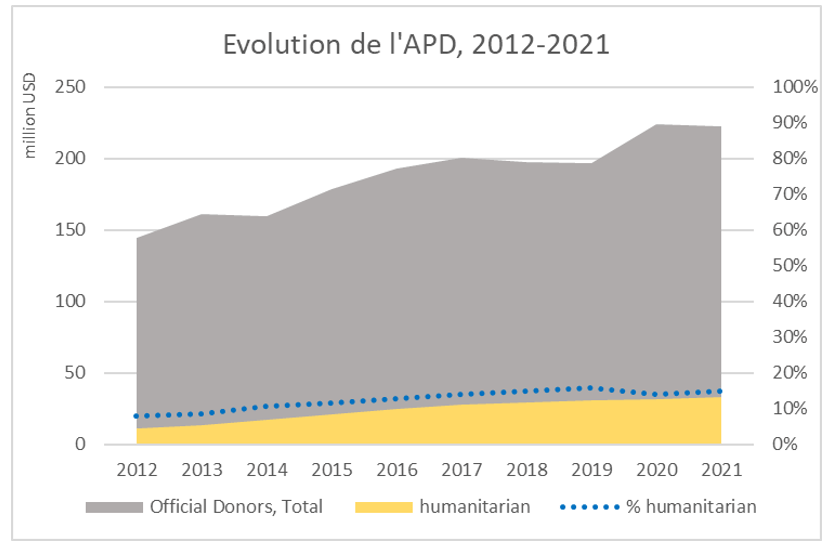

Humanitarian assistance is a category of ODA like other types of aid. Humanitarian assistance continues to grow steadily (Figure 1), recognising that these figures predate the start of the war in Ukraine. It is likely that the share of humanitarian aid will increase much more significantly in 2022. Whether this is a temporary spike or the beginning of a new plateau remains to be seen.

Overall humanitarian ODA increased by 6% between 2020 and 2021, while ODA from DAC countries increased by 20%. The DAC thus remains the financial pillar of the humanitarian system, funding 71% of the USD 33 billion of global humanitarian ODA. Only eight DAC members covered 76% of the 2021 consolidated humanitarian appeals, reflecting the extreme concentration of the financial base of the humanitarian system. Calls to broaden this base have had little effect. Gulf donors are the most involved in a humanitarian effort, although aid remains unpredictable and geographically highly concentrated.

Humanitarian aid now accounts for 15% of both global and DAC ODA, with large disparities by donor country. The table below shows the amount of total ODA, the amount of humanitarian ODA (gross disbursements, constant prices, USD 2020), the share of humanitarian ODA for DAC members and some others, as well as the percentage change between 2020 and 2021.

This growth in humanitarian ODA is driven by the United States, which consolidates its position as the largest humanitarian donor ($11.8 billion), with an increase of 38% compared to 2020. The massive increase in humanitarian ODA from Japan is notable (+139% over USD 1 billion in 2021).

For all donors, the share of humanitarian ODA for Asia – including the Middle East (US$16.4 billion) far exceeds that allocated to Africa (US$9 billion), confirming a long-standing trend, although the gap is slowly narrowing. DAC countries have allocated roughly equivalent amounts of humanitarian aid to Africa and Asia ($7.4 billion and $7.8 billion respectively). The multilateral system is more present in Africa (2.3 billion) than in Asia (1.9 billion) and it is the non-DAC donors who, with their support to the Middle East, make the geographical difference (6.7 billion in Asia against 73 million in Africa).

Unsurprisingly, Afghanistan is the largest recipient of overall humanitarian aid in Central Asia, increasing from 0.5 billion to 2 billion between 2020 and 2021, questioning the capacity of the humanitarian system to absorb a 300% increase in a context as politically and logistically constrained as Afghanistan. This humanitarian increase is part of an overall ODA that has remained more or less stable, between 4 and 4.5 billion per year since 2015. Humanitarian assistance is therefore gradually replacing development when there is no longer any cooperation or dialogue possible around development objectives. DAC members provide the vast majority of this humanitarian aid, with a pronounced lack of interest from non-DAC donors, particularly Gulf donors, in humanitarian aid in this country.

In 2021, Syria will still be the largest recipient of humanitarian aid, although it is beginning to decline from a historic peak of 9 billion in 2020 to 7 billion in 2021. Unlike Afghanistan, where infrastructure projects were still being implemented at the beginning of 2021, 90% of ODA in Syria is already humanitarian, leaving only residual development projects. Here, non-DAC donors are very present, with USD 5.4 billion in 2021, well above the USD 1.5 billion of DAC countries.

The share of humanitarian aid in Europe (USD 1 billion), in 2021, consisted almost exclusively of aid to refugees in Turkey (USD 0.8 billion). Humanitarian aid to Ukraine had increased in 2015 (298 million) and then steadily decreased to 137 million in 2021.

Overall humanitarian ODA to Africa amounts to 9.8 billion in 2021, an increase of 17% compared to 2020. The main recipient countries remain the same, with a significant increase in Ethiopia, from 770 million in 2020 to 1.3 billion in 2021. Humanitarian aid to Somalia (USD 668 million), South Sudan (USD 990 million), Mali (USD 179 million) declines very slightly, and increases slightly in Niger (USD 224 million).

A striking fact for the sector as a whole is the massive increase in regional projects between 2020 and 2021, from USD 99 to 220 million in Africa, from USD 125 to 415 million in South America, from USD 10 to 208 million in Central Asia or from USD 98 to 238 million in the Middle East. This phenomenon reflects the difficulties of intervening directly in the heart of crises, but also the decreasing number of forced displacements in the regions bordering the crises.

In recent years, humanitarian assistance has become one of the most important tools for donors to respond to crises in countries where there is no longer any real cooperation, i.e. no political dialogue between donors and countries that are now less of a ‘partner country’ than a source of political, security and migration concerns. What to do then in countries that are increasingly openly rejecting the development model and the ‘values’ proposed by a limited number of countries that hold the development system at arm’s length. This is a difficult question and an impossible answer, which explains the more or less direct support to populations through humanitarian aid, pretending that it is neutral and does not carry with it a corpus of Western values.

Cyprien Fabre.

Cyprien Fabre is the Head of the Crisis and Fragility Unit at the OECD. A former Solidarités volunteer, then head of several offices for DG ECHO, he joined the OECD in 2016 to analyse the engagement of Development Assistance Committee members in fragile countries and refine the contribution of development assistance to peace objectives in crisis contexts.

Cyprien Fabre is the Head of the Crisis and Fragility Unit at the OECD. A former Solidarités volunteer, then head of several offices for DG ECHO, he joined the OECD in 2016 to analyse the engagement of Development Assistance Committee members in fragile countries and refine the contribution of development assistance to peace objectives in crisis contexts.